American Institutes for Research

KT Update

An e-newsletter from the Center on Knowledge Translation for Disability and Rehabilitation Research

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The contents of this newsletter were developed under grant number 90DP0027 from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this newsletter do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. Copyright © 2017 by American Institutes for Research |

Community of Practice on Evidence for

|

Communicating Science: Tools for

|

Don't miss the

|

Knowledge Translation CasebookWe're excited to announce the launch of the 3rd Edition of the KT Casebook! Take a look to see how NIDILRR grantees are using innovative, effective and measured KT strategies to ensure their research is useful to their audiences.

Many thanks to those who submitted entries to this edition of the KT Casebook, for an opportunity to showcase your KT activities. If you are part of a NIDILRR project, please consider submitting an entry for the 4th Edition of the KT Casebook to: Ann Outlaw |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2017 Online KT ConferenceKTDRR's 2017 Online KT Conference will be held on October 30, November 1, and November 3, 2017, following our pattern of Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. This year's conference theme focuses on effective measurement solutions for your KT outcomes, and includes sessions providing an overview of “KT 101” strategies and examples; social media measurement tools and strategies; and KT outcome measurement tools and strategies. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This issue of KT Update presents another in a series from Dr. Marcel Dijkers. This article describes the origin of PROSPERO (an international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews in health and social care) and PRISMA-P (a listing of preferred reporting items for a protocol for a systematic review or meta-analysis). PROSPERO and PRISMA-PMarcel Dijkers, PhD, FACRM [ Download PDF version 329kb ] It must have been two decades ago that, during the discussion period for a paper that I was presenting at a conference, a colleague remarked something like, “Dr. Dijkers tortures the data until it confesses.” He meant that as a compliment, and that’s how I took it. In hindsight, I would say that he approved that I habitually engaged in data dredging, selective reporting, and various other unsavory tactics to make it possible to report at least one significant p-value—the holy grail of simplistic research. We (or at least I) have since learned about the deleterious effects of publication bias, switching the primary outcome of studies for a secondary one and vice versa, selective reporting of outcomes, (unplanned) subgroup analyses, and so on. Registering TrialsAlready back in the 1970s a proposal was made to register trials as a (partial) antidote to these shady tactics, which aim to make investigators, their studies, and (sometimes) their sponsors look their best. The reasoning went as follows: If researchers register their study protocols before they enroll the first subject, that permanent record makes it possible to determine what studies have not been published, or which ones in their reporting make unjustified changes to a protocol or statistical analysis plan. Pressure from biomedical journal editors, researchers themselves (especially those engaged in creating systematic reviews [SRs]), and governmental and nongovernmental sponsors of research, as well as the Food and Drug Administration and other regulatory agencies, resulted in the creation of registries such as ClinicalTrials.gov, which began operation in 2000. These trial registries work in a very simple fashion. A researcher about to start a study creates (voluntarily or forced by her sponsor or the journal in which he wants to publish) an entry for the study, completing a number of fields with administrative and design information. This minimal protocol can be changed if realities on the ground make that necessary, but the registry keeps all versions on display; as a result, for anyone curious to know how the published data relate to the original research plan, there is a paper trail to follow back. ClinicalTrials.gov and other national and international registries have largely lived up to expectations and now there is an ongoing discussion whether researchers should also be required to submit to the website all or at least summary data from their studies. This would satisfy a second purpose of registries: the public availability of information on research sponsored with public or private funds and involving the volunteer time and effort of hundreds—if not thousands—of subjects. PROSPEROClinical trials and other primary studies are not the only research that may undergo selective reporting. There is now a modest body of research demonstrating that SRs also may be reported selectively, for instance, Kirkham, Altman, & Williamson, 2010; Silagy, Middleton, & Hopewell, 2002; and Siontis, Hernandez-Boussard, & Ioannidis, 2013. Because SRs increasingly are considered the most comprehensive and least biased evidence for use in Evidence Based Practice and Evidence Based Medicine (EBP & EBM) (at the apex of the “evidence pyramid”), that is of no small concern. And a parallel solution has been suggested: the prospective registration of SRs. Although there are multiple registries for primary research, for SRs there is only one: PROSPERO—International prospective register of systematic reviews. While the name suggests “PROSPEctive Register,” I have found no mention of the origin of the appellation; maybe it was borrowed from Shakespeare, whose Prospero (in The Tempest) was a sorcerer. PROSPERO is financed by the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and run by the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. After an international Delphi project to determine what elements should be contained in the registry (Booth et al., 2011), PROSPERO opened for business in 2011 and quickly started cataloguing more than 90 SRs per month (Booth et al., 2013; Booth, 2013); now (February 2017) it contains more than 20,000 records, of which more than 1,300 concern rehabilitation and disability. The concept of registering SRs, or the PROSPERO site specifically, has been endorsed by a number of entities, including the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, which has gone as far as requiring applicants seeking grant funding for a trial to conduct an SR to demonstrate the need for the trial (Graham, 2012). Others include Guidelines International Network (Van der Wees et al., 2012); NIHR (Davies, 2012); and the Public Library of Science journals (Booth et al., 2012), as well as journals such as Open Medicine (Palepu, Kendall, & Moher, 2011), British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (Chien, Khan, & Siassakos, 2012), and Systematic Reviews (Booth et al., 2012). Also on board are organizations such as the International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment and the international Campbell and Cochrane Collaborations (Booth et al., 2012). The PROSPERO registry has a number of major purposes:

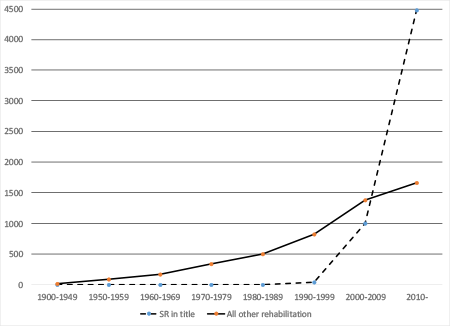

Duplication is not an imaginary problem. The number of SRs being published each year is mushrooming (even in the area of rehabilitation; see Figure 1), and overlapping SRs are not an uncommon phenomenon. Replication is something to be desired, but, as Moher (2013) pointedly asks, how much replication is too much? Figure 1. Number of PubMed entries of “rehabilitation” articles with “systematic review” in the title, and number of all other “rehabilitation” articles, by time period *[ Larger View | Long Text Description ] Numbers for "other rehabilitation" articles have been divided by 100 to make trends clear. PROSPERO works in a way similar to the clinical trial registries: A researcher who wants to register an SR submits administrative and scientific information to the website. These SRs may focus on “health and social care, welfare, public health, education, crime, justice, and international development, as long as there is a health related outcome” (PROSPERO, 2016, p. 3), but scoping reviews and literature reviews are not eligible. The information submitted gets a quick administrative review (Right type of study? Sufficiently clear and informative entries in all required and optional fields?), and when approved (typically, in a few business days) becomes publicly available. Registering an SR is free, as is searching the registry for information. Registration should happen before the systematic reviewers start extracting information from the primary studies, but there is some flexibility. Cochrane protocols are automatically added to PROSPERO (Moher, 2013). Table 1 contains an overview of the items on initial registration; there are 22 required and 18 optional fields, and it is estimated that registration takes about 60 minutes—even less for researchers who already have a written protocol (Booth et al., 2012). Table 1. Required and optional fields for a PROSPERO registration* indicates a required field

NOTE: Adapted from PROSPERO, 2016, pp. 7–21. Slightly modified from the document Guidance notes for registering a systematic review protocol with PROSPERO from the website PROSPERO – International prospective register of systematic reviews. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/aboutreg.php Any changes in the protocol (SRs often undergo changes because of information found or not found in the literature) are to be submitted, and the paper trail is kept for public inspection. PROSPERO sends investigators e-mails to remind them to update their registration as stages in the review are completed (Booth & Stewart, 2013). It also encourages users to submit their published paper or other report to the website once the study is complete. PRISMA and PRISMA-PWhich brings us to PRISMA-P. PRISMA stands for “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses,” and it was first published in 2009 to offer authors guidance on how to report their systematic reviews (Liberati et al., 2009; Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & PRISMA Group, 2009). Under Methods, PRISMA suggests reporting an SR’s “Protocol and registration: item 5: Indicate if a review protocol exists, if and where it can be accessed (e.g., Web address), and, if available, provide registration information including registration number” (Moher et al., 2009, p. 339). The authors of PRISMA suggested that this information be provided because they recognized how important it was for reviewers and readers of an SR to have the opportunity to compare the plan with the actuality, and to be able to determine changes in review methodology as well as selective reporting. They have now gone a step further and have published specific guidance for the contents of such a protocol: the final P of PRISMA-P stands for protocol (Moher et al., 2015; Shamseer et al., 2015). As do all the other members of the PRISMA family, PRISMA-P comes in the form of a checklist, which authors can use to determine whether they have included all relevant items in their protocol (see Table 2). It consists of 17 items—26 if subitems are counted as separate entities (see Table 2). Completing a protocol is expected to benefit SR authors, funders of secondary research, clinical practice guidelines developers, policymakers, journal editors, and peer reviewers, as well as educators and students (Moher et al., 2015; Palepu et al., 2011; Stewart, Moher, & Shekelle, 2012). Table 2. PRISMA-P: preferred items for reporting the protocols for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Source: Moher et al., 2015.

With manuscript page numbers entered, authors can submit the PRISMA-P checklist along with their protocol manuscript to a journal such as Systematic Reviews to make review of their manuscript easier for the editors and peer reviewers. Such publication of protocols is increasingly common; in January 2017, more than 150 were published (as shown in a PubMed search), of which 189 concerned rehabilitation and disability topics. The PRISMA-P authors structured the checklist in such a way that a protocol can easily be turned into a report on the results of the SR or meta-analysis: the items are harmonized with the PRISMA items (Moher et al., 2015). PRISMA-P is intended primarily for the preparation of protocols for reviews of aggregate data reported in the literature. It is not optimal for meta-analysis of individual patient/participant data, the topic of a previous KT Update article (Dijkers, 2016), but it would not be surprising if PRISMA-IPDMA were to follow in the near future. If the objective is to go on public record to declare the aim and methods of an SR, registration on PROSPERO and a published manuscript following the guidance of PRISMA-P seem duplicative but cannot hurt. If sunshine (the opportunity for or threat of public scrutiny) helps to keep researchers, including SR authors, on the straight and narrow, then more sunshine should be welcome. In the end, it is better for all patients, participants, clients, and subjects for whom we write our SRs. ReferencesBooth, A. (2013). PROSPERO's progress and activities 2012/13. Systematic Reviews, 2, 111-4053-2-111. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-2-111 Booth, A., Clarke, M., Dooley, G., Ghersi, D., Moher, D., Petticrew, M.,... Stewart, L. (2012). The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: An international prospective register of systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 1, 2-4053-1-2. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-1-2 Booth, A., Clarke, M., Dooley, G., Ghersi, D., Moher, D., Petticrew, M., & Stewart, L. (2013). PROSPERO at one year: An evaluation of its utility. Systematic Reviews, 2, 4-4053-2-4. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-2-4 Booth, A., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Moher, D., Petticrew, M., & Stewart, L. (2011). Establishing a minimum dataset for prospective registration of systematic reviews: An international consultation. PLOS ONE, 6(11), e27319. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027319 Booth, A., & Stewart, L. (2013). Trusting researchers to use open trial registers such as PROSPERO responsibly. The BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 347, f5870. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5870 Chang, S. M., & Slutsky, J. (2012). Debunking myths of protocol registration. Systematic Reviews, 1, 4-4053-1-4. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-1-4 Chien, P. F., Khan, K. S., & Siassakos, D. (2012). Registration of systematic reviews: PROSPERO. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 119(8), 903-905. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03242.x ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved from https://clinicaltrials.gov Davies, S. (2012). The importance of PROSPERO to the National Institute for Health Research. Systematic Reviews, 1, 5-4053-1-5. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-1-5 Dijkers, M. (2016). IPDMA: Individual Patient/Participant Data Meta-Analysis. KT Update, 4(7). Retrieved from https://ktdrr.org/products/update/v4n7/dijkers_ktupdate_v4n7_508.pdf Graham, I. D. (2012). Knowledge synthesis and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Systematic Reviews, 1, 6-4053-1-6. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-1-6 Kirkham, J. J., Altman, D. G., & Williamson, P. R. (2010). Bias due to changes in specified outcomes during the systematic review process. PLOS ONE, 5(3), e9810. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009810 Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gotzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P.,... Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), e1–34. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 Moher, D. (2013). The problem of duplicate systematic reviews. The BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 347, f5040. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5040 Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. The BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 339, b2535. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535 Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M.,... PRISMA-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4, 1-4053-4-1. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 Moher, D., Tetzlaff, J., Tricco, A. C., Sampson, M., & Altman, D. G. (2007). Epidemiology and reporting characteristics of systematic reviews. PLOS Medicine, 4(3), e78. doi:06-PLME-RA-0453R3 [pii]; 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040078 Palepu, A., Kendall, C., & Moher, D. (2011). Open Medicine endorses PROSPERO. Open Medicine, 5(1), e65-6. PROSPERO—International prospective register of systematic reviews. Retrieved from http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ PROSPERO. (2016). Guidance notes for registering a systematic review protocol with PROSPERO. York, UK: NIHR Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York. Retrieved from Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M.,... PRISMA-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. The BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 349, g7647. doi:10.1136/bmj.g7647 Silagy, C. A., Middleton, P., & Hopewell, S. (2002). Publishing protocols of systematic reviews: Comparing what was done to what was planned. JAMA, 287(21), 2831–2834. doi:joc11902 Siontis, K. C., Hernandez-Boussard, T., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2013). Overlapping meta-analyses on the same topic: Survey of published studies. The BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 347, f4501. doi:10.1136/bmj.f4501 Stewart, L., Moher, D., & Shekelle, P. (2012). Why prospective registration of systematic reviews makes sense. Systematic Reviews, 1, 7-4053-1-7. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-1-7 Van der Wees, P., Qaseem, A., Kaila, M., Ollenschlaeger, G., Rosenfeld, R., & Board of Trustees of the Guidelines International Network (G-I-N). (2012). Prospective systematic review registration: Perspective from the Guidelines International Network (G-I-N). Systematic Reviews, 1, 3-4053-1-3. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-1-3 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||