Bladder ✓ Mobile Application

National Capital Spinal Cord Injury Model System

MedStar Health Research Institute

Submitted by Amanda K. Rounds

Focus

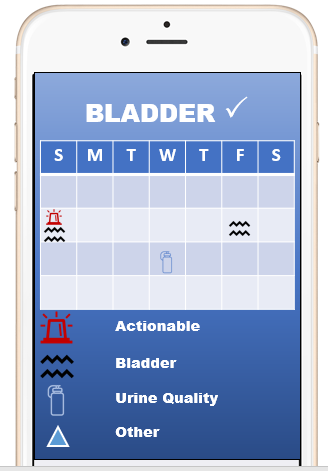

We used a patient-centered, patient-reported outcomes (PC-PRO) approach to develop three urinary symptom questionnaires for neurogenic bladder (USQNBs). These USQNBs are now being transformed into the Bladder ✓ mobile application. The app will give consumers an accessible and easy-to-use way to monitor their bladder health.

Context

The National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) funds our team for the Bladder Rehabilitation Research Training Center and National Capital Spinal Cord Injury Model System. Our team is composed of national leaders in the field of research on bladder dysfunction and urinary symptoms after nervous system injury or disease. We are located at MedStar National Rehabilitation Hospital in Washington, DC.

Consumers report that bladder health and function is a major research priority.1 “Today people are dying from common secondary complications of SCI [spinal cord injury], and this has not changed in 40 years. . . . [T]he scientific community . . . [has] an obligation to address these issues despite being scientifically complex.”1 Urinary tract infection (UTI) is the most common outpatient infection in the world, particularly among people with neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (NLUTD) or neurogenic bladder. UTI is also the most common infection, secondary condition, cause for emergency room visits, and infectious cause of hospitalization.2–5 Despite its prevalence, attempts to reduce cases of UTI among people with NLUTD are stymied by long-standing challenges that arise from evidence gaps around diagnostic tests (urinalysis and urine culture) that are considered the “gold standard.” These tests, however, have lower sensitivity and specificity for UTI in those with SCI and NLUTD. These challenges persist despite coordinated efforts by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research,6 the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,7 the European Association of Urology8 with other European and Asian urologic societies,8,9 and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.10 These organizations have created guidelines about the prevention of catheter-associated UTI, but efforts have not promoted criteria to diagnose UTI.8,10 All guidelines note a lack of high-quality evidence to support such criteria, and each guideline calls for research to address the challenge of diagnosing UTIs.11

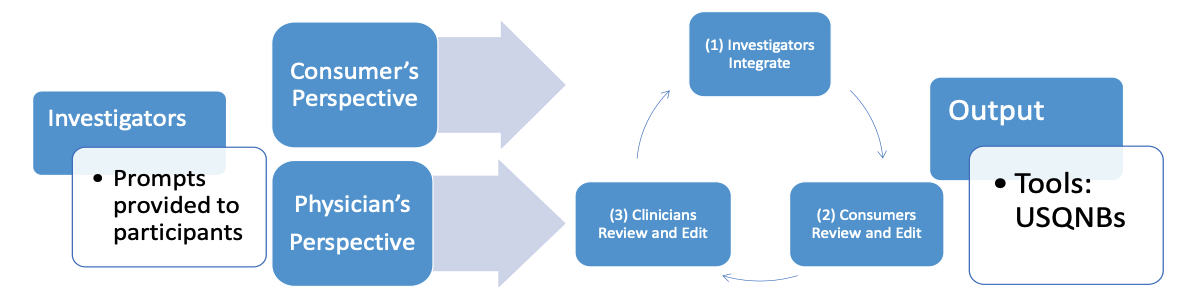

To address this problem, our team, from 2014 to 2020, used a PC-PRO approach to develop three USQNBs. Each USQNB is based on a person’s bladder management method: void (no catheter), intermittent catheter, and indwelling catheter.12–16 These instruments allow consumers to monitor themselves for symptoms of UTI. The instruments grew out of an iterative process involving focus groups and semi structured interviews (Figure 1). The process captured patients’ experiences with and clinicians’ perspectives of UTI symptoms. More details about the process are described in Tractenberg et al., 2018.12

Figure 1: PC-PRO model used to create USQNBs

Source: Tractenberg et al., 201812

USQNB decision aid and Bladder ✓ app

QR Code

to access all USQNBs

The USQNBs enable consumers to monitor themselves for symptoms of UTI. The three instruments cover the range of urinary symptoms based on a person’s bladder management method: void (no catheter), intermittent catheter, or indwelling catheter. Consumers can use the chart on page 2 of each instrument as a decision-making tool to help them act when they experience one or more symptoms:

- “Consider seeking medical attention for UTI assessment,”

- “Consider seeking medical attention for assessment of symptoms,”

- “Consider medical assessment of bladder function,”

- “Self-manage and monitor symptoms,” and

- “Monitor and consider seeking medical assessment.”

USQNB Impact and evaluation of the Bladder ✓ app

Research is already showing the positive impact the USQNBs has for consumers to intervene when experiencing urinary symptoms.12–15,17,18 The Bladder app bridges years of research to create a tangible decision-making aid for consumers who struggle with UTIs. Overall, the app will help consumers feel more knowledgeable and autonomous in maintaining a healthy bladder.

To develop the app, we will use the same PC-PRO iterative approach as was used to develop the USQNBs. We will also develop a sustainability plan to get feedback from consumers at each stage of development (e.g., wireframes and beta testing). Consumer feedback will ensure every aspect of the app—from the interface to the export options and the action outputs—is designed for easy use and accessibility for all consumers. When the app is near completion, we will bring it to market through a plan with our long-standing relationships with consumer advocacy groups.

Contact Information

NIDILRR Grant Name: National Capital Spinal Cord Injury Model System

Organization: MedStar Health Research Institute

Mailing Address: 102 Irving St NW, Washington, DC, 20010

Website: https://www.medstarhealth.org/mhri/medstar-research-networks/medstar-neuroscience-and-rehab-research-network/bladder-rehabilitation-research-training-center/

Key contact: Amanda K. Rounds, PhD, (author), Amanda.K.Rounds@medstar.net

References

- Morse, L. R., Field-Fote, E. C., Contreras-Vidal, J., Noble-Haeusslein, L. J., Rodreick, M., Shields, R. K., Sofroniew, M., Wudlick, R., Zanca, J. M., & SCI 2020 Working Group. (2021). Meeting proceedings for SCI 2020: Launching a decade of disruption in spinal cord injury research. Journal of Neurotrauma, 38(9), 1251–1266. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2020.7174

- Cardenas, D. D., Moore, K. N., Dannels-McClure, A., Scelza, W. M., Graves, D. E., Brooks, M., Busch, A. K. (2011). Intermittent catheterization with a hydrophilic-coated catheter delays urinary tract infections in acute spinal cord injury: A prospective, randomized, multicenter trial. PM & R, 3(5), 408–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.01.001

- Haisma, J. A., van der Woude, L. H., Stam, H. J., Bergen, M. P., Sluis, T. A., Post, M. W., Bussmann, J. B. (2007). Complications following spinal cord injury: Occurrence and risk factors in a longitudinal study during and after inpatient rehabilitation. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 39(5), 393–398. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0067

- Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. (2006). Bladder management for adults with spinal cord injury: A clinical practice guideline for health-care providers (Clinical Practice Guidelines: Bladder Management). Paralyzed Veterans of America. https://pvasamediaprd.blob.core.windows.net/prod/libraries/media/pva/library/publications/cpgbladdermanageme_1ac7b4.pdf

- DeJong, G., Tian, W., Hsieh, C-H., Junn, C., Karam, C., Ballard, P. M.,. Smout, R. J., Horn, S. D., Zanca, J. M., Heinemann, A. W., Hammond, F. M., & Backus, D. (2013). Rehospitalization in the first year of traumatic spinal cord injury after discharge from medical rehabilitation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 94(4), S87–S97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2012.10.037

- The prevention and management of urinary tract infections among people with spinal cord injuries (National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Consensus Statement, January 27–29, 1992). (1992). The Journal of the American Paraplegia Society, 15(3), 194–207. doi:10.1080/01952307.1992.11735873

- Vickrey BG, Shekelle P, Morton S, Clark K, Pathak M, Kamberg C. (1999). 6. Prevention and management of urinary tract infections in paralyzed persons: Summary. In AHRQ evidence report summaries. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11881/

- Stöhrer, M., Blok, B., Castro-Diaz, D., Chartier-Kastler, E., Del Popolo, G., Kramer, G., Pannek, J., Radziszewski, P., & Wyndaele, J-J. (2009). EAU guidelines on neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. European Urology, 56(1), 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2009.04.028

- Tenke, P., Kovacs, B., Bjerklund Johansen, T. E., Matsumoto, T., Tambyah, P. A., & Naber, K. G. (2008). European and Asian guidelines on management and prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 31(Suppl 1), S68–S78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.033

- Hooton, T. M., Bradley, S. F., Cardenas, D. D., Colgan, R., Geerlings, S. E., Rice, J. C., Saint, S., Schaeffer, A. J., Tambayh, P. A., Tenke, P., & Nicolle, L. E. (2010). Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 international clinical practice guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 50(5), 625–663. https://doi.org/10.1086/650482

- Health.gov. (n.d.). Health care-associated infections. https://health.gov/hcq/prevent-hai.asp

- Tractenberg, R. E., Groah, S. L., Rounds, A. K., Ljungberg, I. H., & Schladen, M. M. (2018). Preliminary validation of a urinary symptom questionnaire for individuals with neuropathic bladder using intermittent catheterization (USQNB-IC): A patient-centered patient reported outcome. PLoS ONE, 13(7), e0197568. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197568

- Tractenberg, R. E., Frost, J., Rounds, A. K., Yumoto, F., Ljungberg, I. H, & Groah, S. L. (in press). Reliability of the urinary symptom questionnaires for people with neurogenic bladder (USQNB) who void or use indwelling catheters. Spinal Cord.

- Tractenberg, R. E., Frost, J., Rounds, A. K., Yumoto, F., Ljungberg, I. H., & Groah, S. L. (in press). Validity of the urinary symptom questionnaires for people with neurogenic bladder (USQNB) who void or use indwelling catheters. Spinal Cord.

- Tractenberg, R. E., Groah, S. L., Rounds, A. K., Davis, E. G., Ljungberg, I. H., Frost, J. K., & Schladen, M. M. (2020). Clinical profiles and symptom burden estimates to support decision-making using the urinary symptom questionnaire for people with neurogenic bladder (USQNB) using intermittent catheters. PM & R, 13(3), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmrj.12479

- Tractenberg, R. E., Frost, J. K., Rounds, A. K., Yumoto, F., Ljungberg, I. H., & Groah, S. L. (in preparation). Assessment along the continuum of neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (NLUTD) with the urinary symptom questionnaires for individuals with neurogenic bladder (USQNBs).

- Groah, S. L., Tractenberg, R. E., Rounds, A. K., Frost, J., Ljungberg, I.H., Davis, E., Schladen, M.M. (in revisions). Urinary symptoms and urine dipstick self-assessment are unassociated in individuals SCI, MS, and NLUTD who void. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation.

- Rounds, A. K., Tractenberg, R. E., Groah, S. L., Frost, J., Ljungberg, I.H., Navia, H, Pham, C., et al. (in review). Urinary symptoms are unrelated to leukocyte esterase and nitrite among indwelling catheter users.